From the Book “Atlas Ilustrado de los Tercios Españoles en Flandes”, Susaeta Ediciones SA

Uniformidad y banderas

Los soldados de los Tercios no dispusieron de uniforme tal y como lo entendemos hoy en día. Por aquel entonces, la vestimenta no difería de la de uso civil y, para identificarse en la batalla, bastaba con que los combatientes bordasen en la parte superior de su traje una cruz encarnada de San Andrés –en forma de aspa–, o portasen en su brazo un trozo de tela atada de un determinado color. Mientras los franceses solían utilizar el azul, los españoles usaban preferentemente el rojo, ambos colores propios de las respectivas casas reales.

Aunque las pinturas de época apenas reflejan esta realidad, las ropas eran más bien modestas y de colores sobrios. Los tratadistas se quejan del siniestro efecto que producía ver a la infantería española teñida de negro con los paños raídos. Se contaba con pocas mudas y se reservaba siempre la de mejor calidad para las paradas y días de fiesta. De hecho, en ocasiones la intendencia adquiría prendas al por mayor para distribuir entre la tropa, la cual se les descontaba luego del sueldo, como se hacía con el armamento.

Esto se practicaba con la intención de reducir las bajas causadas por la crudeza del invierno. Por otro lado, existe un testimonio de que el duque de Alba vestía de azul celeste para ser fácilmente reconocido.

Uniformity and Flags (Traducttion)

The soldiers of the Tercios did not have a uniform as we understand it today. At that time, the clothing was no different from civilian clothing, and to identify themselves in battle, combatants simply had to embroider a red Saint Andrew’s cross (in the shape of a saltire) on the top of their uniform or carry a piece of cloth of a specific color tied around their arm. While the French usually wore blue, the Spanish preferred red, both colors representing their respective royal houses.

Although period paintings barely reflect this reality, the clothing was rather modest and of sober colors. Authors complain of the sinister effect produced by seeing the Spanish infantry dyed black with their threadbare cloth. There were few changes of clothing, and the best quality was always reserved for parades and holidays. In fact, sometimes the quartermaster would purchase clothing in bulk to distribute among the troops, which was then deducted from their pay, as was done with weapons.

This was done with the intention of reducing casualties caused by the harshness of winter. Furthermore, there is evidence that the Duke of Alba wore sky blue to be easily recognized.

Now, that’s what the book says about the Tercios. In theory, their clothing could be ragged, but they must have worn at least some red or military heraldry, so as not to be mistaken for beggars, bandits, or enemy troops.

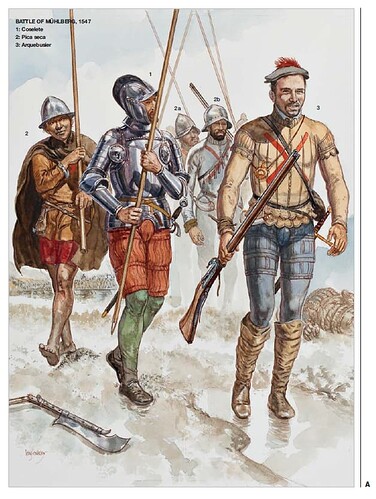

As for whether they wore a Morion-type helmet or not, “well, it depends,” since, as they say, “there was no basic uniform,” and the quality of the weapon depended on the soldier’s salary. In fact, if they had money, they could have worn a Morion; if not, a small cap. In this Osprey image, “Tercios,” there are two early Spanish arquebusiers, one with more money than the other.

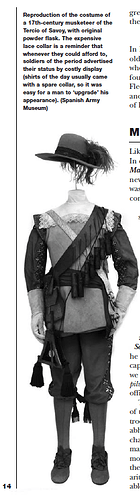

Unlike the arquebusiers, the musketeers used such heavy weapons that they didn’t actually wear metal helmets, but rather caps. It could be an artistic license to differentiate them by choosing longer hats for the musketeers, although we could also consider that “a better cap” is synonymous with “having more money.” Therefore, since the musketeers were Spaniards with more money to buy a musket, they would have been able to buy a better cap (as compensation for not wearing a helmet).

On the other hand, since the musketeer was a recent and, in fact, expensive weapon, musketeer corps were not used as much in the early years of the Tercio. It was only when the cost of manufacturing them decreased that entire musketeer corps began to be created to replace the arquebusiers. But we’re talking about 1615 onward, and I think we’d already be outside the game’s period.