This is a proposal of a classical type of DLC, meant to fill a hole from that region with:

- 2 civs: Serbians/Serbs & Romanians/Vlachs

- 1 architecture set: Byzantine (Byzantines, Bulgarians, Armenians, Georgians, Serbs)

- 3 campaigns: Matthias Corvinus (Magyars), Mehmed the conqueror (Turks), Stefan Dušan (Serbs)

I am not a good player so a lot of these balances may be off, feel free to let me know what should be changed.

Civs:

1. Serbians - Monk and Siege civ

Philosophy: The Serbian Church was very important in the medieval age as the Serbs were very religious people, during Ottoman times the Church was the closest thing the Serbs had to independence, they were often walled and autonomous. But even before the Ottomans the church played a significant role in Serbian history, much more so than for other Orthodox countries save Russia. The Serbs also had giganic mining towns and were able to form the Serbian Empire by defeating the Byzantine Empire’s fortifications. (see the campaign proposal). As such, I envision them as a straight-forward Monk and Siege civilization. Which would lead to a lot of interesting anti-meta gameplay. As for the unique unit, while the Hajduk became more romanticized in the 17th century, they existed as early as the 14th cenutry and would be in my opinion one of the most iconic units of the Serbs.

Civilization Bonuses

- Wood and Gold miners work 5% faster.

- Petards available in Siege Workshop

- Can research Siege Engineers in Castle Age

- Monks cost -30 gold

- Fortified Church replaces Monastery

- Villagers work 5% faster when near Fortified Church and can garrison in Fortified Church.

Unique Technologies

- Vojnici → Spearmen line gets +1 attack and +1 armor.

- Serbian Vineyards → Fortified Churches slowly generate food.

Team Bonus

- Mangonel-line +2 line of sight

Unique Unit:

- Hajduk. (Infantry)

Food: 50

Gold: 30

Training time: 16 seconds

Hit points: 50

Melee attack: 11

Attack bonus: +4 vs Spearmen-line

Melee armor: 1

Range-armor: 3

Movement Speed: 1.15

Line of Sight: 8

I do not know if my stats proposal are appropriately balanced. I propose Hajduk has a unit with a speed as high as Eagle Warriors, larger line of sight than an average infantry unit, lower attack than Champions, as much melee Armor as Champions, good versus Archers, beating Spear-man line but losing to hard infantry and cavalry. To deal with Cavarly the Serbs also have the Vojnici unique technology.

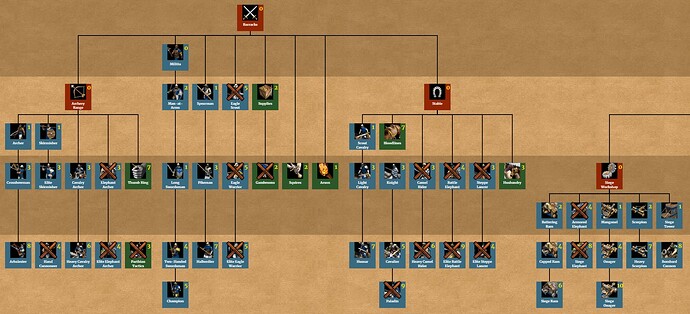

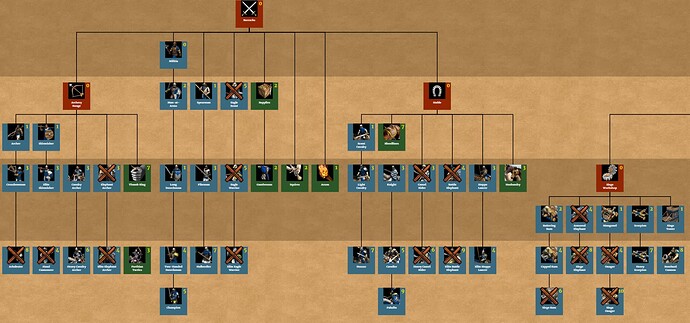

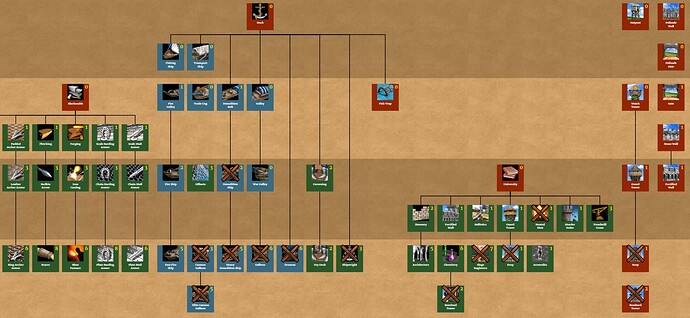

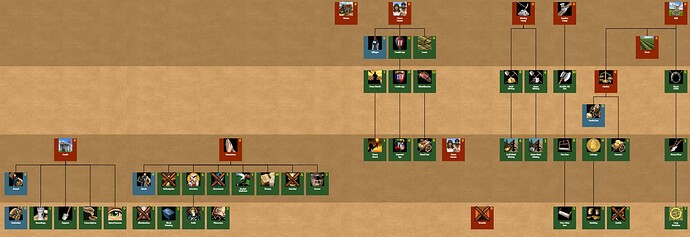

Tech Tree:

2. Romanians - Cavalry and Trash civ

Philosophy: The Romanians being at the borderline between east and west had units from both cultures. They were not developed economically when compared to their neighbours but invested a lot in their army, with peasants having mandatory training in using weapons and professional soldiers getting the best gear that they could afford. The large host being the trained peasants and the small host being the professional army. Which I would translate as having above-average units but weak economy. They were mostly shepherds and farmer and during the Ottoman times they were never integrated in the Ottoman empire because they were very hard to invade. As for the unique unit, I propose something that emphasizes the west-east combination, Calarasi.

Civilization Bonuses

- Start with +2 sheeps

- Units do not take elevantion bonus damage

- Spearmen-line and Skirmisher-line gets +1 attack

- Receive back 20% of the resources of buildings destroyed by an enemy.

Unique Technologies

- Mărgineni → +2 food and wood carry capacity for villagers.

- Venetian Weapons → Knight-line gets +1 attack and +1 armor.

Team Bonus

- Cavalry gets +2 damage to buildings.

Unique Unit:

- Calarasi. (Cavalry Archer)

Wood: 50

Gold: 70

Training time: 23 seconds

Hit points: 65

Pierce attack: 7

Attack bonus: +4 vs Cavalry

Reload time: 2

Accuracy: 50%

Melee armor: 0

Range-armor: 0

Movement Speed: 1.25

Line of Sight: 5

I propose Calarasi to be a Horse Archer specialized against Cavalry, slightly more tanky than a regular Cavalry Archer and with +1 damage but with lower speed, slower than a Paladin even. This will make them either stronger than a regular Cavalry Archer or weaker depending on the situation. It’s a bit of tankiness from the west combined with the hit and run style from the east, while being master of none.

Tech Tree:

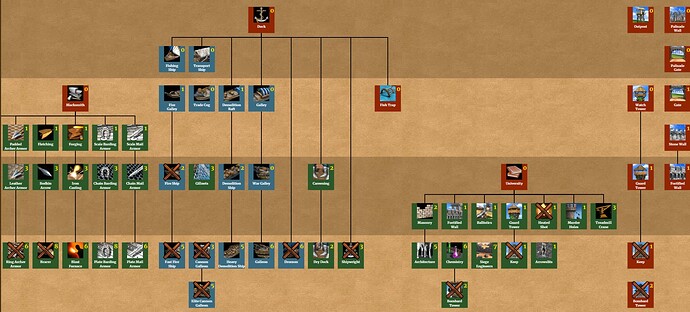

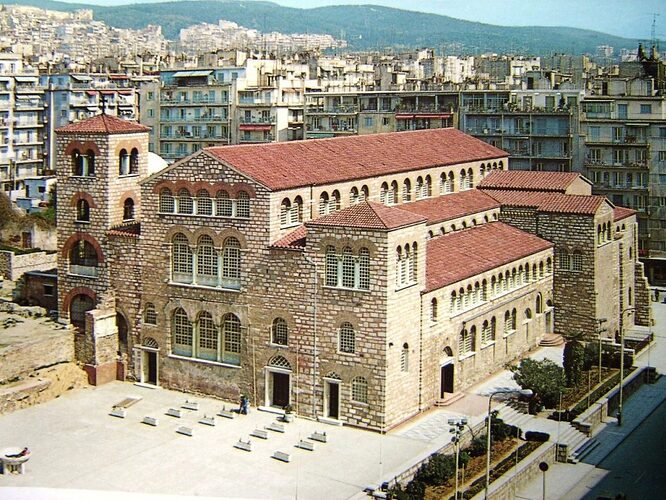

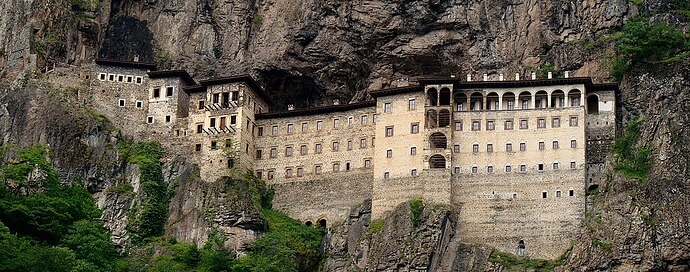

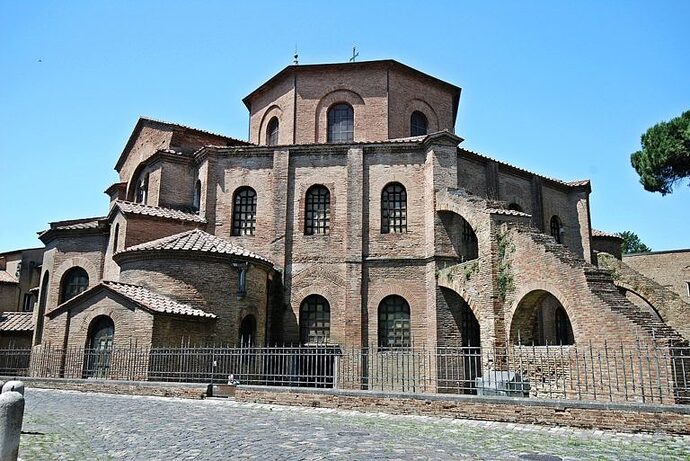

Byzantine Architecture Set

This new architecture can be used by the: Byzantines, Bulgarians, Armenians, Georgians and Serbs.

Example from a mod:

Campaigns:

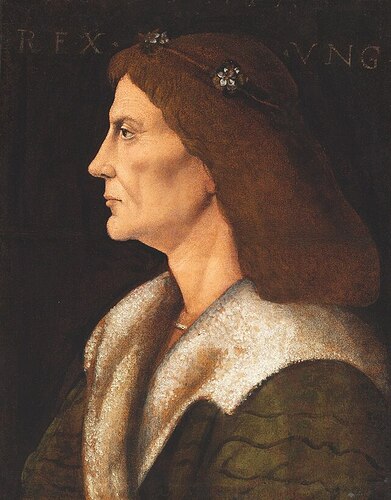

1. Matthias Corvinus (Magyars)

Matthias Corvinus (1443–1490), born Mátyás Hunyadi, was the second son of the renowned Hungarian military leader John Hunyadi. His early life was shaped by the political turbulence of 15th-century Hungary. After his father’s death in 1456 and the execution of his older brother Ladislaus in 1457, Matthias found himself at the center of Hungary’s complex power struggles. He was elected King of Hungary in 1458 at the age of 14, becoming the first ruler of non-noble birth to ascend the Hungarian throne—a testament to his family’s immense influence.

As king, Matthias worked tirelessly to strengthen royal authority and centralize power. He was a reformer, an astute diplomat, and a military genius. Known as the “Raven King” (Corvinus derives from “corvus,” Latin for raven), he adopted the raven as his emblem, a symbol of wisdom and vigilance.

Possible Missions:

-

Moldavian Campaign: The Defeat at Baia (1467)

Matthias launched a campaign against Stephen the Great of Moldavia in 1467, aiming to assert Hungary’s dominance over the region. However, the campaign ended disastrously for Matthias at the Battle of Baia. The Moldavian forces ambushed and inflicted heavy casualties on the Hungarian army, forcing Matthias to retreat wounded. Despite this setback, Matthias leveraged his propaganda machine to portray the campaign as a victory, emphasizing his survival and framing the retreat as a strategic withdrawal. This episode illustrates his ability to manage public perception and maintain his political authority even after defeat. -

Campaign Against the Ottomans: The Siege of Szabács (1476)

Matthias Corvinus continued his father’s mission to defend Hungary from Ottoman expansion. One of his notable victories came in 1476 with the Siege of Szabács, a key fortress on the southern border. Matthias launched a well-coordinated attack, combining naval forces and infantry to capture the stronghold. This victory bolstered Hungary’s defensive line and demonstrated his tactical brilliance. However, it was not a definitive blow to the Ottomans, as their power in the Balkans remained unchallenged overall. -

The Bohemian War: Claiming the Bohemian Crown (1468–1479)

Matthias engaged in a protracted conflict with George of Poděbrady, the Hussite King of Bohemia, as part of his ambition to expand Hungary’s influence. In 1468, Matthias launched a military campaign under the pretext of defending Catholicism against Poděbrady’s Hussite beliefs. By 1469, he was crowned King of Bohemia, though his control extended only over Moravia, Silesia, and Lusatia. The conflict dragged on until the Treaty of Olomouc (1479), which divided Bohemian lands between Matthias and Vladislaus II of Poland, the new Bohemian king. While not a complete victory, Matthias secured significant territories and prestige. -

The Venetian Campaign: Dalmatian Successes (1479)

Matthias also directed his attention toward the Adriatic coast, where Hungary competed with Venice for control of Dalmatian cities. In 1479, Hungarian forces achieved a significant victory at the Battle of Breadfield, where they crushed a Turkish raiding force allied with Venice. This campaign solidified Hungary’s influence in Dalmatia and underscored Matthias’s ability to manage multiple fronts simultaneously. The victory was celebrated as a triumph of Hungarian strength against both Ottoman and Venetian ambitions. -

Campaign Against Emperor Frederick III: Conquest of Vienna (1485)

Matthias’s rivalry with Emperor Frederick III of the Holy Roman Empire culminated in his audacious conquest of Vienna in 1485. This campaign began as part of Matthias’s efforts to assert dominance over Austria, a region historically contested between the Habsburgs and Hungary. After a prolonged siege, Matthias’s forces captured Vienna, which became his residence and a cultural hub of his court. This marked the high point of Matthias’s territorial expansion, though it strained Hungary’s resources. His rule in Vienna solidified his reputation as a powerful Central European monarch.

2. Mehmed the conqueror (Turks)

Sultan Mehmed II (1432–1481), known as “Mehmed the Conqueror,” was one of the most influential rulers of the Ottoman Empire. Ascending the throne at the age of 12 and later reclaiming it in 1451, Mehmed pursued an ambitious vision of expanding the empire. His most celebrated achievement came in 1453 with the conquest of Constantinople, earning him the title “Conqueror” and marking the end of the Byzantine Empire. This monumental victory transformed the Ottomans into a global power and established Istanbul as the empire’s new capital.

A brilliant strategist and administrator, Mehmed centralized Ottoman governance, overhauled its military, and patronized science and the arts, solidifying the empire’s foundations. His campaigns stretched across the Balkans, Anatolia, and even Italy, demonstrating his relentless ambition to dominate both Europe and Asia. Mehmed’s reign was characterized by his exceptional ability to balance diplomacy, warfare, and statecraft, cementing his legacy as one of history’s great rulers.

-

The Conquest of Constantinople (1453)

The conquest of Constantinople was Mehmed’s defining achievement. After a meticulous preparation involving the construction of the Rumeli Fortress and assembling a massive army of over 80,000 troops, Mehmed laid siege to the city. Employing innovative tactics, including the use of giant cannons to breach the city’s formidable Theodosian Walls, Mehmed achieved victory on May 29, 1453. This campaign not only ended the Byzantine Empire but also established Istanbul as the Ottoman capital, transforming it into a cultural and economic hub of the empire. -

The Campaign Against Vlad the Impaler (1462)

In 1462, Mehmed launched a campaign against Vlad the Impaler, the voivode of Wallachia, who had rebelled against Ottoman suzerainty. Vlad’s guerrilla tactics, including his infamous “Night Attack” on Mehmed’s camp, inflicted heavy casualties. However, Mehmed’s overwhelming forces eventually forced Vlad to retreat. The Ottomans captured Târgoviște, where they discovered Vlad’s infamous “forest of the impaled,” showcasing his cruelty. Though Vlad escaped, this campaign reinforced Ottoman control over Wallachia and demonstrated Mehmed’s determination to crush dissent. -

The Albanian Wars Against Skanderbeg (1443–1468)

Mehmed faced fierce resistance from Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg, the Albanian leader who defied Ottoman rule. Skanderbeg used the mountainous terrain of Albania to conduct effective guerrilla warfare, winning key victories at Krujë. Despite Mehmed’s superior numbers and repeated sieges of Krujë (notably in 1466–1467), Skanderbeg’s forces successfully defended their stronghold. Mehmed’s failure to subdue Albania delayed the Ottoman expansion into the Adriatic region, and Skanderbeg became a symbol of resistance against Ottoman domination. -

Campaign Against Stephen the Great of Moldavia (1476)

Mehmed’s 1476 campaign against Stephen the Great of Moldavia followed the Moldavian voivode’s refusal to submit to Ottoman suzerainty. After Stephen defeated an earlier Ottoman force at the Battle of Vaslui (1475), Mehmed personally led a massive army to retaliate. At the Battle of Valea Albă (Războieni), the Ottomans achieved a decisive victory, forcing Stephen to retreat into the mountains. However, logistical challenges and Moldavian guerrilla resistance prevented Mehmed from fully subjugating Moldavia, making it a costly campaign for the Ottomans. -

The Otranto Campaign (1480)

Late in his reign, Mehmed turned his attention to Italy, aiming to expand Ottoman influence in Europe. In 1480, his forces captured the city of Otranto, establishing a foothold in southern Italy. While the campaign alarmed European powers, Mehmed’s sudden death in 1481 curtailed Ottoman ambitions in Italy. Although short-lived, this campaign demonstrated Mehmed’s vision of extending Ottoman reach into the heart of Christendom.

Stefan Dušan (Serbs)

Stefan Dušan (1308–1355), known as Dušan the Mighty, was the greatest ruler of medieval Serbia, reigning as king from 1331 and later as Emperor of the Serbs and Greeks from 1346 until his death. His reign marked the height of the Serbian Empire, during which Serbia became the most powerful state in the Balkans. Known for his military prowess, legal reforms, and ambition to unite the Orthodox Christian world, Dušan sought to expand Serbian dominance into the territories of the declining Byzantine Empire.

In addition to his conquests, Dušan introduced the Dušan’s Code in 1349, one of the most comprehensive legal frameworks of its time. This code aimed to unify his diverse empire under a single set of laws, blending Byzantine legal traditions with Serbian practices. Dušan’s reign left a profound legacy, not only in expanding Serbian territory but also in fostering a cultural and legal foundation that influenced the region long after his death.

-

The Overthrow of His Father (1331)

Stefan Dušan’s rise to power began with a decisive campaign against his father, Stefan Dečanski, who had alienated much of the Serbian nobility. Dušan led a military revolt, defeated his father’s forces, and claimed the throne. This internal conflict set the stage for Dušan’s later expansionist campaigns, as he consolidated power and secured the loyalty of Serbia’s nobles and army. -

Conquests in Macedonia (1334)

One of Dušan’s earliest campaigns was against the Byzantine Empire, capitalizing on its internal instability. In 1334, Dušan invaded Macedonia and captured several key cities, including Ohrid and Prilep. These victories established Serbia as a major power in the Balkans and marked the beginning of Dušan’s systematic encroachment on Byzantine territories. The campaign demonstrated his ability to exploit Byzantine weakness and expand Serbian influence in the region. -

Campaign Against the Byzantines: Capture of Serres (1345)

In his push toward Constantinople, Dušan focused on consolidating his hold over the Byzantine territories of Macedonia and Thrace. In 1345, his forces captured the city of Serres, a major fortress and strategic location. This victory further weakened Byzantine authority in the region and bolstered Dušan’s claim to imperial legitimacy. Following this success, he proclaimed himself Emperor of the Serbs and Greeks, formalizing his ambition to replace the Byzantines as the preeminent Orthodox Christian power. -

The Conquest of Epirus and Thessaly (1348)

Dušan’s most significant territorial gains came during his 1348 campaign in Epirus and Thessaly, where he expanded Serbian control deep into Byzantine Greece. This campaign brought key cities like Ioannina and Larissa under Serbian rule. By this time, Dušan’s empire stretched from the Danube to the Aegean, making Serbia the dominant Balkan power. These conquests were critical to Dušan’s vision of creating a Serbian-led Byzantine Empire. -

Alliance with Venice and Campaign Against the Ottomans (1354)

Toward the end of his reign, Dušan sought to forge alliances against the rising Ottoman threat. In 1354, he negotiated with Venice to create a coalition to halt Ottoman expansion into Europe. Although he prepared for a campaign against the Ottomans, his untimely death in 1355 prevented its execution. This unrealized campaign could have significantly altered the course of Balkan history, as Dušan’s leadership was seen as a crucial counterbalance to Ottoman ambitions.