First of all, I don’t speak neither English nor Spanish as my native language. So please bear with me if I make any grammar or puctuation mistakes.

This is just a conceptual suggestion, that’s why the thread will only address bonuses, unique units and techs. Specific bonus values and the tech tree can always be tweaked for balance later.

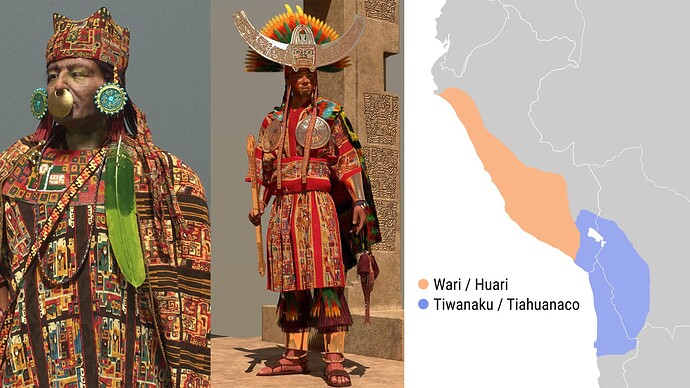

The Wari or Huari

Why the Wari empire?

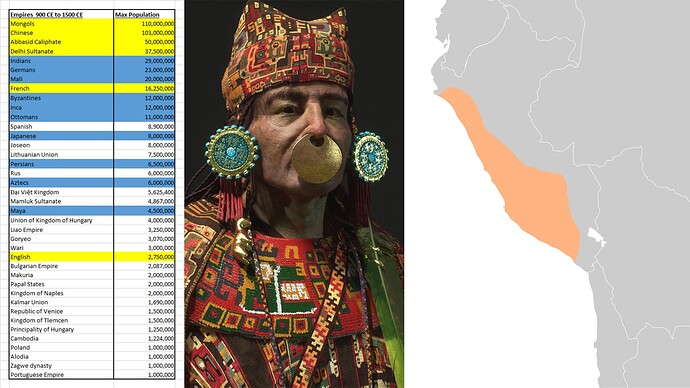

-It was the first empire of the Andes, the first true empire of the Americas, and the second largest empire in all the history of the New World.

-The Wari empire was a bronze age civilization that later united with the Tiwanaku.

-The Wari empire alone had a population of 3 million and encompassed about 700 000 km2. During the Tiwanaku-Wari period, the empire was approx. 1 300 000 km2 and the population is estimated around 5.2 million before their collapse by the end of the Middle Horizon era.

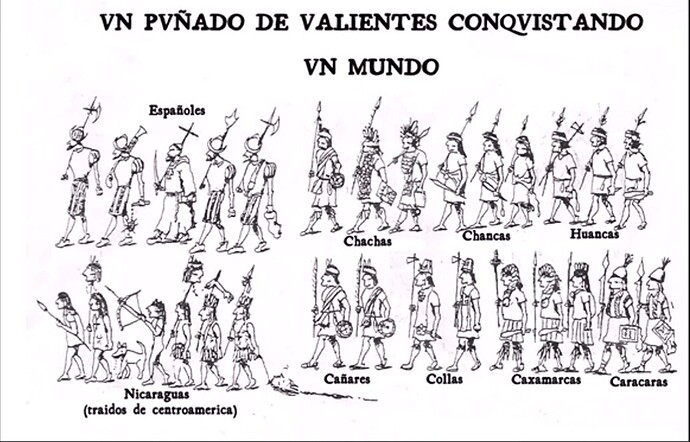

-Technically, they are already in-game as the Chankas (Inca campaign and history section) and somewhat as the Huancas (Inca history section).

-The Wari empire is unique and has enough personality to be a new civ. It was an aggresive expansionist andean empire populated by multi-ethnic people who spoke yunga, quechua and aymara.

-Among American civs: The Aztecs’ role is offensive infantry and monks. The Mayans’ role is offensive archers. The Incas’ role is counter units.

The Wari could take the offensive skirmishers and team support role.

Civ concept: Infantry and skirmishers.

-Infantry technologies are X% cheaper.

-Lumberjacks generate X gold per second while in gathering animation.

-Can build Pikillaqta and research: Andenes and Tiwanaku priests.

Unique units

-

Kunka Kuchuna (or Neck breaker): Fast infantry that increases his attack per hit. Stacks X times.

-

Chukiq Awqaruna (or Andean javelineer): Multipurpose skirmisher that also has attack bonus vs unique units. Available at the archery range since the Castle age.

Unique techs

- Bronze tupus (Castle age): Skirmishers gain +1 meele armor and are trained X% faster.

- Wiracocha cult (Imperial age): Eagle warriors regenerate X HP per min and attack X% faster.

Unique building

Pikillaqta: Highly resistant Wari settlement that can train villagers and trade carts, but can’t attack. It can increase the defense of nearby buildings by X%. Building it costs gold and stone. Available since the Castle age.

Team bonus

Barrack units +X LOS

Civ techs

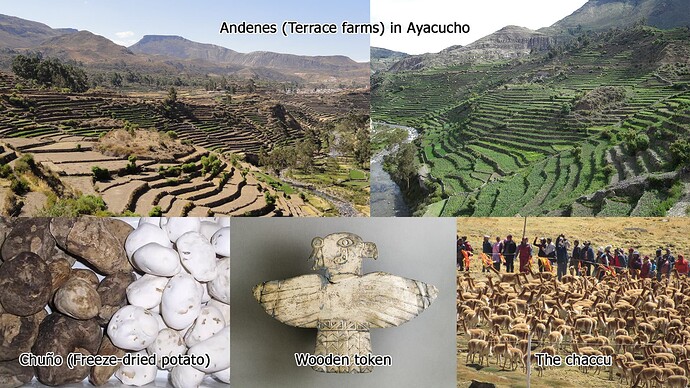

Andenes (Feudal age): For the Wari, farms last X% longer. For all teammates, farms cost -5 wood. It can be researched at the mill.

Tiwanaku priests (Castle age): For the wari, monks regenerate their faith X% faster. For all teammates, monk-type units move 5% faster. It can be researched at the monastery.

Possible wonders:

-Huarmey castle.

-Wiracochapampa.

-Vegachayuq Moqo.

-Huaca Pucllana.

-Cahuachi.

Architecture: Andean (shared with the Incas).

Notes:

There is one reference to the Tiwanaku because of their confederation.

The andean javelineer perhaps could have +2 or 3 vs cavalry and eagles.

Historical background

Just if you are interested in reading it.

About the Wari (Chankas) from Aoe II:

The Inca were the rulers of the last great Amerindian empire of South America, and the creators of the largest Pre-Columbian state of the Americas. Originally a small tribe from the Cuzco region of Peru, the Inca formed a kingdom that by the early 15th century became a major power in the central Andes. In 1438, their power was challenged by the Kingdom of the Chanca, whose leader disliked their growing cultural supremacy. The Inca repelled the Chanca invasion and, in response, went on a massive uninterrupted period of expansion that lasted for nearly a century.

In 1438, the Inca Empire was established by Pachacuti Inca in the aftermath of the failed Chanca invasion.

About the Wari empire:

In the 16th century, Spanish conquistador and chronicler Pedro Cieza de León wrote «Cronicas del Peru», one of the most importart history and ethnography books about the New World in that century. Cieza de León describes pre-columbian ethnic groups and their achievements; which are known today as the Chimu and Chan-Chan city (chap. LXVIII), the Lima and Pachacamac temple (Chap. LXXII), the Nazca and the Nazca lines (chap. LXXV), the Chavin and Huantar temple (chap. LXXXII), and the Wari and Viñaque (chap. LXXXVII). This is the first mention of the Wari empire in scholar literature. In 1903, the German archaeologist Friedrich Max Uhle publishes «Pachacamac» after rigurous studies in Lurin valley. Because of new ceramic, metal and textile discoveries in the Andes, he was the first to suggest the Tiwanakus were trading with the north and allied with an unknown andean culture. Today, we know those artifacts belonged to the Wari. In 1935, the Peruvian archaeologist Julio C. Tello studied this unknown culture, today known as the Wari. In 1936, Julio C. Tello, together with prominent American archaeologists Alfred Kroeber, Samuel Lothrop, Wendell C. Bennett, and others established the Institute of Andean Research (IAR) to study the Wari and other andean cultures. In the middle of the 20th century, studies and archeological investigations led by Wendell C. Bennett and Rafael Larco Hoyle concluded the Wari culture was more advanced than Tiwanaku. In 1957, archaeologist Luis G. Lumbreras proposed the theory of the Wari being an empire. Later that same year, the archaeologist and anthropologist John H. Rowe submitted a theory that also supported the Wari imperial stage. In 1970, archaeologist Mario Benavides published his book Analisis de la Ceramica Huarpa about the Huarpa culture. In 1984, the archaeologist William Isbell discovered the Wari were older than what was originally thought, and the culture existed as early as the first century (around 100 CE). The architecture shows a long sequence of human occupation that would develop into the well-known Wari urbanism of the 6th century (around 550 CE). In 1988, the archaeologist Ruth Shady Solis published her article «La epoca Huari como interaccion de las sociedades regionales». She suspected that Wari wasn’t an empire, but an economic network that integrated other kingdoms for mutual benefit and supported them with its military. Later in 1997, William Isbell estimated that the early Wari had a population of 10 000-70 000 before their urbanism. In 2001, William Isbell proposed that the Huarpa culture is the early stage of the Wari and categorized it as Pre-Wari. In 2010, the Polish archaeologist Krzysztof Makowski becomes one of the researchers and advisors in The Huarmey Castle project (led by the Polish Milosz Giersz). In 2013, Krzysztof Makowski discovered 63 Wari tombs and more than 1200 artifacts including jewels, utensils, ceramics and bronze weapons. The Wari weren’t as peaceful as Ruth Shady thought. Makowski concludes Wari was without a doubt either an empire or an imperialistic expansionist state, however, he calls it a Failed Empire (from the “Failed State” term) because it was a rich and powerful empire that annexed other kingdoms through conquest but failed to impose the Wari dynastic identity on them. Unlike the Incas and the Chimu, which he calls successful. In 2019, the archaeologist Ismael Perez Calderon supports William Isbell’s theory and describes the Huarpa as the early stage of the Wari empire.

The Huarpa or early Wari period (approx. 200 BCE-500 CE)

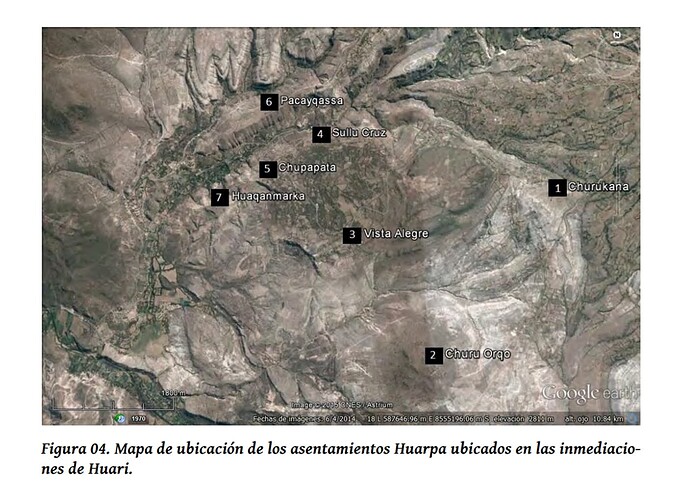

The Huarpa culture was an early Wari society contemporary with the Moche, the Nazca, the Tiwanaku, the Recuay, and the Lima. The Huarpa lived in what is present-day Ayacucho, an arid mountain region surrounded by steep ridges and cliffs in the Andes. The dry and hard soil made it difficult to cultivate plants and raise livestock so, in order to survive, the Huarpa built complex systems of canals and andenes (terrace farms). Their towns lacked urban planning. The Huarpas built and expanded their villages and towns as their population grew.

From 100 AD, the Huarpa cities became more organized with identifiable separate residential and commercial areas. During this time, their population is estimated between 10 000 and 70 000.

The Wari culture period (approx. 500 CE-600 CE)

The Huarpa expanded their area of influence and engaged in commercial activities with coastal cultures like the Nazca of present-day Ica. Their fast economic growth was thanks to their works of artistic craftsmanship. Especially woodcraft, which the Huarpa traded for silver and gold that would later be used during their religious ceremonies held in honor of Kon (winged feline or puma god). As a consequence of needing more efficient government to sustain their expansion, the Huarpas abandoned their towns and founded the city of Wari.

Phase 1A:

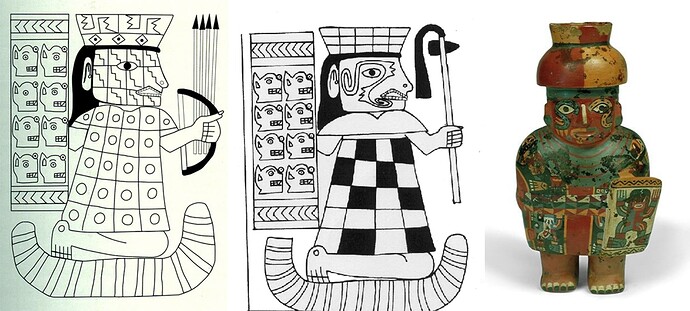

After the foundation of the Wari city, the Wari quickly built several cities of similar size around Wari city to turn it into the capital. Simultaneously, several Wari merchants and craftsmen were sent across the altiplano (andean plateau of South America) in search of new trade routes. It is believed that during this period the Wari were influenced by the Tiwanaku religion and mythology. Therefore, Wari ceramics start to show noticeable Tiwanaku religious influence. The most representative ceramic styles being the «conchopata» and «chakipampa A».

The Wari empire period (approx. 600 CE-1200 CE)

Phase 1B:

This phase was characterized by the radical changes in the Wari socio-political structure. Wari cities grew uncontrollably due to massive migrations from rural areas. This strengthened the Wari state economically, but also causes the necessity to expand its frontiers. The Wari began their expansion towards the west: first they annexed Huamanga valley by force. Then, they assembled a group of Wari merchants, accompanied by an army, and sent them to the Nazca kingdom. The Wari wanted to impose their products through intimidation but ended up destroying the Nazca capital, annexing the kingdom, and appointing a Nazca noble as governor. The archaeologist Luis G. Lumbreras believes this was Wari’s modus operandi because mummies of merchants surrounded by weapons have been found in mausoleums dedicated to the military class. The Wari culture has traditionally been seen as warlike in nature. The empire then expanded towards the north and conquered the Lima, the Huanca, the Yungas and the Recuay kingdoms. They build several planned and designed urban centers such as Honqo pampa and Willcawain in present-day Callejon de Huaylas, Wiracochapampa and Marcahuamachuco in present-day La Libertad, and Pikillaqta in present-day Cuzco. The Wari also built the temples of Wariwilca, Jincamoco and Waywaka in the Mantaro valley, which was part of the Huanca territory, and connected them with the Wari capital through their road network known as Wari Ñan (the precursor of the Inca road system Qhapaq Ñan). The Wari constructions developed further as the conquered cultures influenced their architectural style. In this phase, their ceramics, bronze and wood crafts also developed advanced styles called «Robles moqo», «Chakipampa B» and «Pacheco». It is suggested that around this time, the Wari empire and the Tiwanaku kingdom established a confederation. Although archaeologists Ruth Shady and Dorothy Menzel call it a pseudo-confederation because there is not enough evidence of a confederation. The archaeologist Joyce Marcus suggests Wari and Tiwanaku were neighboring empires that coexisted without conflicts and cooperated with each other, but their political relationship was described as two empires that didn’t go to war with one another for fear of mutual destruction.

Phase 2A and 2B:

In these phases, The Wari reach their maximum expansion of 700 000 km2 approximately and had a population between 2.9 and 3.1 million. The empire continued to conquer other kingdoms, and built periphereal cities such as Jargampata and Azangaro in San Miguel and Huanta respectively. The Wari centralized the empire and imposed their culture on the region. They remodeled the Huaca Pucllana of the Lima culture and turned it into a necropolis for Wari nobles (The lord of the Unkus, and The Lady of the mask). They also turned Cahuachi of the Nazca culture into a Wari ceremonial site.

During phase 2A, their ceramics and crafts developed the styles called «viñaque», «atarque» and «pachacamac». They built the city of Socos in Chillon valley and the city of Conoche in Topara.

During phase 2B, the Wari expanded and conquered the north of South America. It is important to note that the Wari didn’t incorporate the Moche through conquest, but still managed to turn the Moche kingdom into a tributary state. The archaeologist Federico Kauffmann Doig suggests the Moche were annexed as a result of exhaustion from attrition warfare after many years of war without a clear victor. They joined willingly. His theory is based on the fact that moche ceramics abandoned their bicolor tendencies and adopted polychromatic styles of red-black-white patterns, like the Wari, between the periods corresponding to Wari 1B, 2A and 2B. This means the Wari influenced and were in constant contact with the Moche despite being enemies. Kauffmann Doig also suggests the annexation of the Moche may have been a factor to Wari’s decline since the campaigns were too expensive and required large armies over the centuries. The Wari conquered the Cajamarca III culture and the Lambayeque kingdom around 850 CE, which gave them total control of the north.

Phase 3:

In this phase, the Tiwanaku kingdom disbanded around the 11th century after many decades of decline probably caused by alternating periods of droughts and floods caused by El Niño. Most of them migrated towards the north, but decades later those who remained in the altiplano formed several native polities known as the Aymara kingdoms. Meanwhile, the Wari empire gradually became weaker economically due to the unfavorable climate change. The Wari launched a last military expedition towards the South, which used to be part of the Tiwanaku territory, and made contact with the Chiribaya culture. It is unclear whether the Wari conquered them or if there was only a cultural exchange.

Phase 4:

From 1000 CE, Wari cities started to become depopulated. Former conquered kingdoms such as the Lambayeque, the Huanca, the Chancay, the Yungas, and the remains of the Moche cut ties with the Wari empire and became independent again. The Wari empire was reduced to a regional kingdom once more. Finally around 1100 CE, the Wari state disbanded, and the scarcity of food forced the remaining Wari to migrate towards northern regions like the Mantaro and the Ichma valleys. The Wari in Mantaro valley joined the Huanca people and formed a new Huanca kingdom in Wariwilca. The Wari in Ichma valley joined the Pachacamac oracle, while some wandering groups moved south along the coast and joined the Chincha and other states.

The Chanka period (approx. 1200 CE-1438).

The Chankas appeared in present-day Ayacucho around 1000 CE, and made contact with the declining Wari. The archaeologist María Rostworowski suspects the Chankas were a foreign culture that arrived in Ayacucho from towns next to lake Choclococha and Chucurpu highlands in present-day Huancavelica. According to her theory, the Chanka migrations and invasions caused instability in the weakened Wari state and accelerated its collapse. The Chankas were divided into three groups: the Hanan Chankas, or the Upper Chankas, who inhabited Andahuaylas. The Urin Chankas, or the Lower Chankas, who inhabited Uranmarca. The Villca Chankas, or Rukanas, who inhabited Vilcas Huaman in Ayacucho. Those three valleys used to be Wari centers.

For some archaeologists, the Chanka society is a step backwards from the point of view of urban progression, as compared with the Wari culture. Their settlement pattern was the most widespread of small villages (about 100 houses). Other scholars believe, however, that the Chankas had large populations. There are two types of burials: some in mausoleums, and other simply in the ground. There are also burials in caves or rock shelters.

Additionally, the Chankas share some similarities with the Wari. Both societies worshipped a winged puma deity, built mausoleums, painted their faces during combat, had an expansionist culture, and produced polychromatic high-relief pottery.

Controversy: A recent archaeogenetic research shows the Urin and the Villca Chankas are the closest relatives of the Wari, while the Hanan Chankas weren’t related genetically until about 1300 CE. This contradicts María Rostworowski’s theory. Nonetheless, the archaeologist Jose Ochatoma supports María Rostworowski’s theory and suggests that the Chanka invasion did take place but, decades after the collapse of the Wari empire, some wandering Wari groups from the north might have returned to Ayacucho and joined the Hanan Chankas. These wandering Wari being the ancestors of the Urin and Villca Chankas.

The Tiwanaku-Wari period (approx. 6th century-11th century)

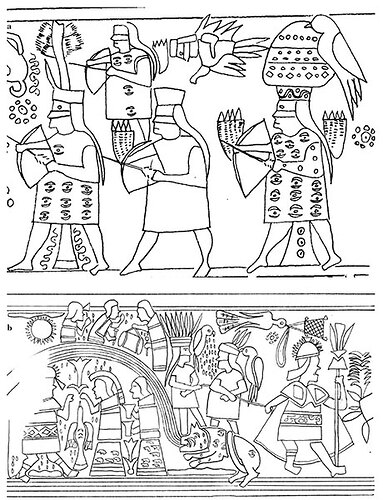

The Tiwanaku-Wari empire was the political union between the Wari empire and the Tiwanaku culture that encompassed more than 1 300 000 km2 and had a population of 5.2 million during the Middle Horizon period. Most archaeologists believe it was an imperialistic confederation controlled by the warmonger Waris because there are no traces of conflict and the Wari road system passes through Tiwanaku territory. On the other hand, there is a group of archaeologists who refute that theory and prefer to call it a pseudo-confederation because there is no clear evidence of a unified government, and they advocate to categorize it as a pacific coexistence between two empires for mutual benefit. The relationship between the two polities is unknown. Definite interaction between the two is proved by their shared iconography in art. The Tiwanaku created a powerful ideology, using previous Andean icons that were widespread throughout their sphere of influence. They used extensive trade routes and shamanistic art. Tiwanaku art consisted of legible, outlined figures depicted in curvilinear style with a naturalistic manner, while Wari art used the same symbols in a more abstract, rectilinear design with a militaristic style.

Economy

The Wari economy was based on agriculture and craftsmanship. They built andenes (terrace farms) to cultivate maize, potatos, oca, mashwa, peanuts, sweet potatos, quinoa, ulluco, etc. They preserved the harvest by exposing the vegetables to very low night temperatures, freezing them, and then leaving them under intense sunlight of the day. The process lasted more than five days, and the result was non-perishable freeze-dried food. The Wari preferred to preserve potatos, and the product was called chuño. The Wari also practiced the chaccu in Pampa Galeras, which consists in shearing vicuñas without harming them.

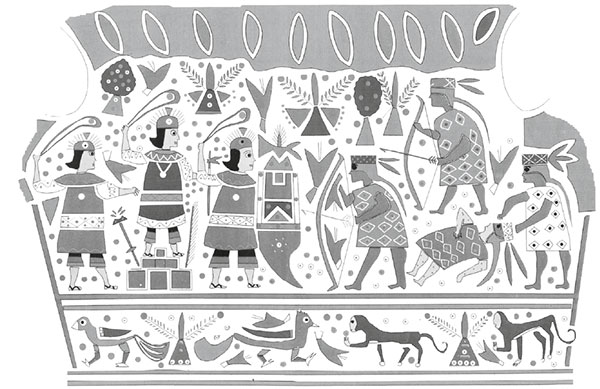

The Wari craftworkers mainly produced ceramics and wooden artifacts. These prestige and luxury goods were traded for metal ores, cotton, llama and vicuña fiber, feathers, seeds, livestock, etc. They also carved religious wooden tokens for other cultures in exchange for silver and gold, implying an incipient business model.

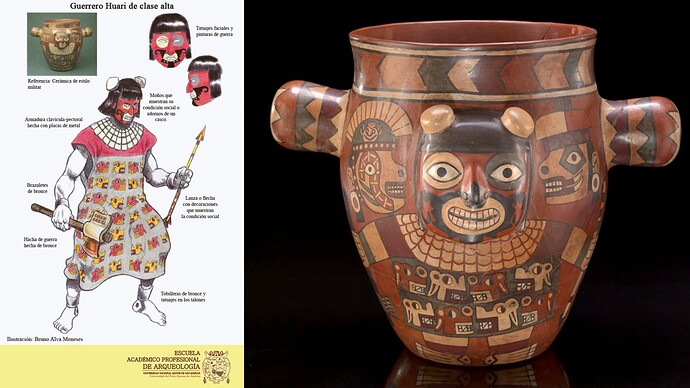

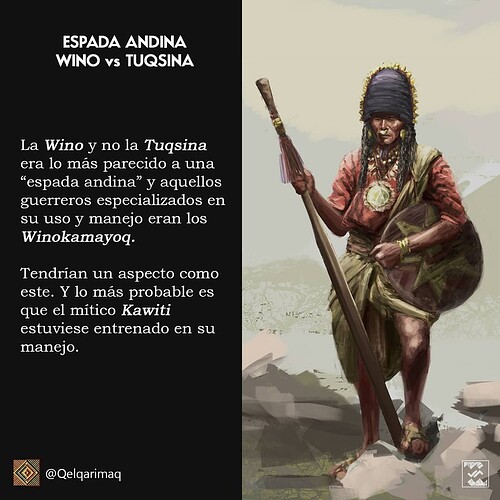

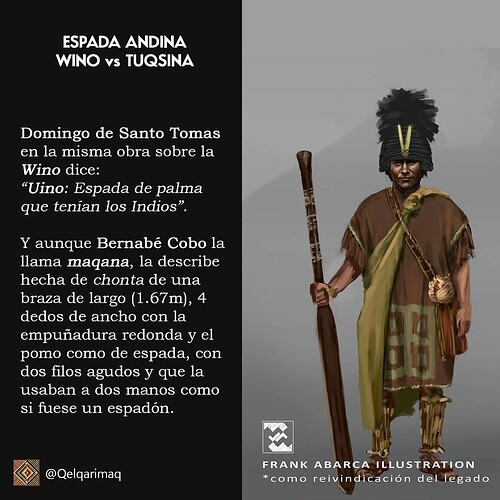

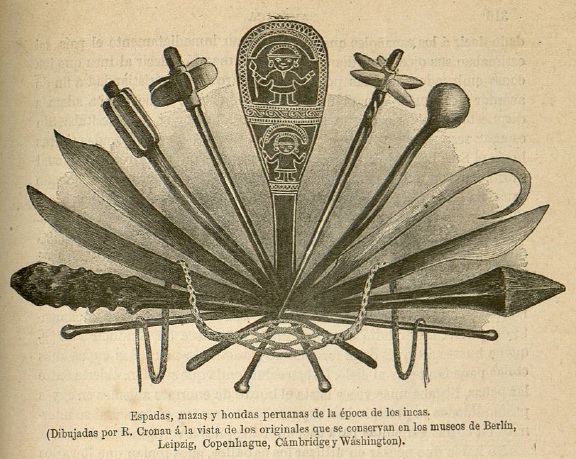

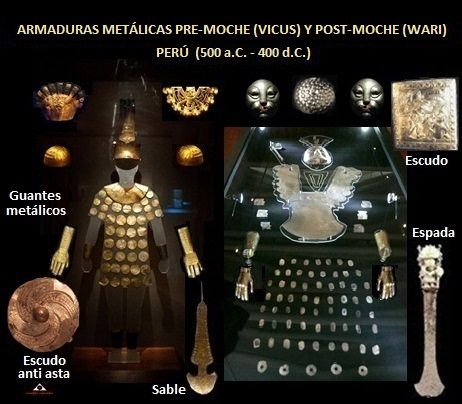

Warfare

Wari is known as the warmonger state of South America in the Middle Horizon era. Not only they had an expansionist culture, but also their army was organized so that their soldiers could be as efficient as possible. Wari warriors were grouped in quinary or decimal systems, depending on their role in battle, and were commanded by a noble of the same expertise. For example, the infantry was grouped in decimals and led by a veteran noble who wielded spears, maces or axes. While the archers and sligers were grouped in quinaries and led by an archer or slinger veteran noble. The army was divided in castes and ranks based on meritocracy and highly rewarded. Warriors of the Wari caste received luxurious rewards such as gold tokens, land, and colorful feathers which were symbols of status. As opposed to warriors conscripted from conquered kingdoms who only received plots of land and livestock. The Wari army also used war paint to rally themselves for battle and played pututu trumpets to cause fear and confusion among the enemy.

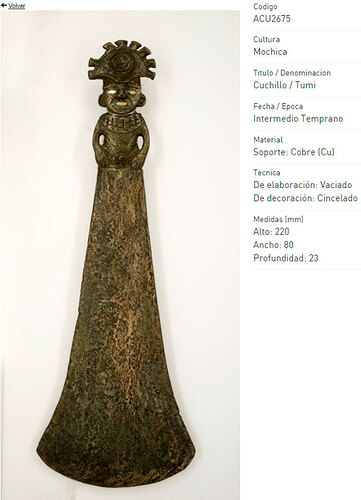

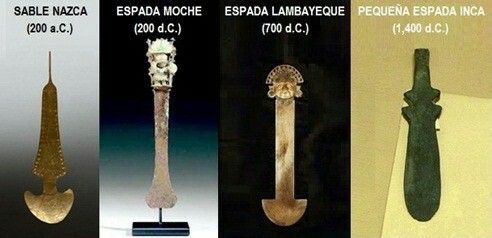

Metallurgy and blacksmithing

There are vestiges of Wari metallurgy in gold, copper and bronze religious figures made via a combination of bossing, plating, lost-wax, hitting and shaping methods. Some authors affirm that Wari metalworking progressed thanks to the Tiwanaku influence; however, Krzysztof Makowski proposes it actually developed in Waywaka, an archaeological site studied by Joel W. Grossman in the Andahuaylas region, where bronze pieces were found. Ismael Perez Calderon suggests the Wari developed further their blacksmithing after annexing the Moche kingdom, and they built blacksmith centers dedicated solely to produce metal equipment and weapons; more specifically in fortified places such as Conchopata and Huarmey Castle.

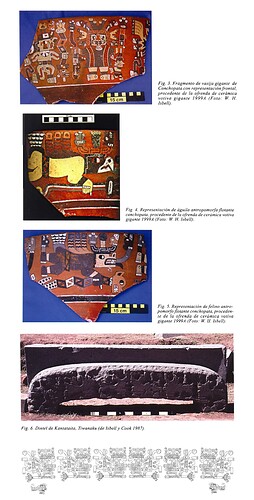

Conchopata

Some of the most complex Wari metallurgical works were found in Conchopata by the archaeologist Denise Pozzi-Escot. The site was a blacksmith workshop mainly dedicated to the working of copper and gold; and its predominant products were «tupus» or «topos». The tupu was a thick metal safety pin used as rivets to strengthen shields and doors, and to keep clothes from falling and getting loose. Tupus were abundant in Conchopata but they were also found in large quantities in Huamachuco, Jargampata and Azangaro, so it’s almost certain they were mass produced. Bronze and silver tupus were also found in Wari city, which indicates that certain materials might have been restricted based on social class.

Huarmey Castle

The fortress, also known as The Castle on the River Huarmey, is a pyramid-like structure on the coast of Peru, in the Ancash Region north of Lima, the most studied section of the archeological complex is the Wari mausoleum which was discovered in an undisturbed condition. The burial chamber of the royal tomb was discovered in early 2013 by a Peruvian-Polish research team, which was led by Milosz Giersz of Poland’s University of Warsaw and co-director Roberto Pimentel Nita. The tomb contained 1,200 artifacts, including gold earrings, bronze axes, jewelry made of copper and silver, and silver bowls. Jose Ochatoma thinks the Castle was heavily protected because it was a Wari necropolis that was surrounded by blacksmith workshops.

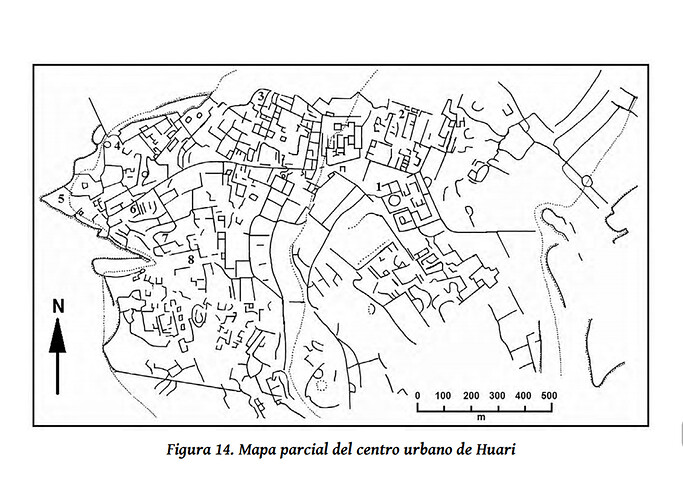

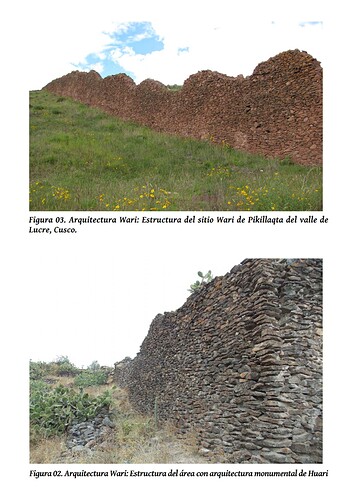

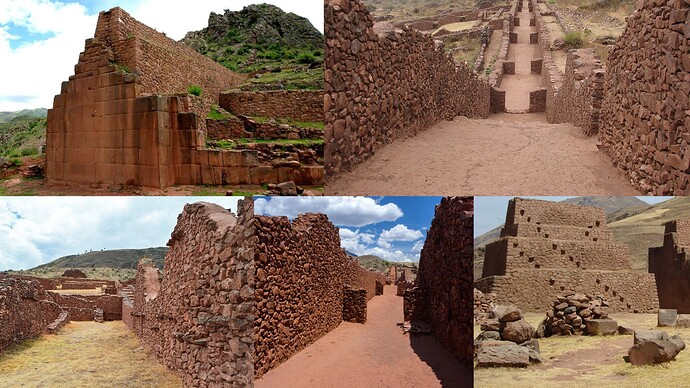

Pikillaqta

Pikillaqta was a large urban center of the Wari people. At around A.D. 650, the Wari erected Pikillaqta, a huge fortified complex covering 25 hectares south of the Cuzco valley. Pikillaqta was garrisoned and all five entrances to the valley accessible from the altiplano were heavily fortified. Pikillaqta may have been large feasting site. There was a large patio or plaza in the middle of the complex that probably was the center of the administrative rituals and religious practices. Rulers and their kin would come together and feast and drink, and with the capacity of the patio, Pikillaqta could hold a ceremony for people from other Wari settlements. Items like turquoise bluish-green stone were traded into the area. They were used for figurines and bluish-green stone was not found in the area. Other stones, gemstones, and minerals were exchanged around the area. Anita Cook suggests Pikillaqta may have been the center of the big trade network. The pottery in Pikillaqta was also traded in, Okros and Huamanga style pottery were two of the main styles and they were made around the area. Pikillaqta was one of the biggest Wari sites so other goods were probably traded in and out of the area and housed in the many buildings at Pikillaqta. Many people came around for the ceremonies so a lot of items were probably traded or brought in with them.

Religion

The Wari religion evolved through their different periods and phases. The first tutelary god of the Waris was Kon, a winged puma god that rejoiced when people waged war. However, influenced by the Tiwanaku, they also worshipped Wiracocha the staff god. During the imperial period, Wiracocha became the most importat god, and the Waris often portrayed him in apotheosis, with hands holding instruments of power, in their ceramics and textiles. A form of the staff god, for example, takes a central role in the Sun Gate of the Tiwanaku culture, a single-stone monolith. Tunics and ceramics from both the Tiwanaku and Wari cultures of the Middle Horizon period showcase a similar god. Another example is the giant offering jars found at Conchopata: They were painted with the Staff-God’s image, one that bears resemblance to the god’s depiction at the back of the Tiwanaku’s Ponce Monolith. The archaeologist Luis G. Lumbreras believes there must have been syncretism between both cults that transformed Wari into a theocratic-militaristic society of zealots during the imperial period. A theory that’s supported by numerous evidence of funerary masks and complex burial chambers, the emergence of necropolis in Huaca Pucllana and Huarmey Castle, and the ceremonial reform in Cahuachi.

Important figures

-The Lord of Vilcabamba: He was a wari warrior-governor who reigned in Vilcabamba valley, Cuzco.

-The Lord of the Unkus: He was a rich wari ruler of the Lima culture. His mummy was found in Huaca Pucllana.

-The Lady of the mask: She was a wari queen of the Lima culture. she was buried in Huaca Pucllana, surrounded by servants and luxurious textiles.

-The Queen of Huarmey: She was a wari warrior-queen who reigned over Ancash. She was buried along bronze axes in Huarmey Castle.

-Uscovilca: He was the founder of the Hanan Chankas.

-Ancovilca: Wari leader who returned to Ayacucho. He was the founder of the Urin Chankas.

-Anccu Hualloc: He was a Chanka leader who launched the conquest of Cusco with 40,000 warriors.

Languages:

Ayacucho quechua (Chanka) and Aymara.

Possible campaigns:

-The Wari and the conquest of South America.

-Update to the Inca campaign: Incas vs Chankas (Wari) and Chimu (Chimu).

Source

Thanks to google translate

-Allison, Malcolm (2011). “El Señor Wari de las selvas de Vilcabamba”. La Mula online.

-Encyclopædia Britannica (2021). “Huari: Archaeological site and Andean civilization”. Encyclopædia Britannica online.

-González Carré, Enrique (2004). “Los Señoríos Chancas: historia, mitos y leyendas”. Boletín del Instituto Riva-Agüero No. 31. PUCP.

-Grossman, Joel W.; Kenna, Timothy C. (2017). “Early Metallurgy from Waywaka in the South-Central Highlands of Andahuaylas, Apurimac, Peru: New AMS Dates and XRF Analysis”. The 81st Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Vancouver, British Columbia.

-Isbell, William H. (1984). “Huari urban prehistory”. En A. Kendall (Ed.), Current Archaeological Projects in the Central Andes. British Archaeological Reports

International Series 210. Oxford.

-Jennings, Justin; Mora, Franco; Velarde, María Inés; Yépez Álvarez, Willy (2015). “Wari imperialism, bronze production, and the formation of the Middle Horizon: Complicating the picture”. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology.

-Lumbreras, Luis G. (1980). “El Imperio Wari”. En Historia del Perú, vol. 2, pp. 9–91. Editorial J. Mejia Baca, Lima.

-Makowski, Krzysztof; Giersz, Milosz (2014). “Castillo de Huarmey. The Wari Imperial Mausoleum”. Asociación Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI).

-Rowe, John H.; Collier, Donald (1950).“Reconnaissance notes on the site of Huari, near Ayacucho, Peru”. American Antiquity, Salt Lake City.

-Pérez Calderón, I. (2019). “El estado regional Huarpa y los orígenes del Imperio Wari”. Alteritas, (9), 181 - 221.

-Santa Cruz, Javier Fonseca; Bauer, Brian S. (2020). “The Wari Enclave of Espiritu Pampa”. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press at UCLA.

-Valdez, Lidio M.; Valdez, J. Ernesto (2021). “Archaeological research in a rural settlement in the Ayacucho Valley, Peru”. ARQUEOLOGÍA Y SOCIEDAD Nº 33, 2021: 75-106. UNMSM.

-Vergano, Dan (2013). “‘Temple of the dead’ discovered in Peru”. USA TODAY online.

-Wikipedia (2021). “Cultura wari”. Wikipedia online. Spanish.

-Wikipedia (2021). “Huari”. Wikipedia online. Italian.

-Wikipedia (2021). “Wari Empire”. Wikipedia online. English.